hipSYCL: The first single-pass SYCL implementation with unified code representation

Heterogeneous Utopia?

- Imagine you didn’t have to specify any targets when compiling with SYCL.

- Imagine compilation took not much longer than a regular clang compilation for your CPU.

- Imagine the resulting SYCL binary could run on CPUs - but also magically on any NVIDIA, Intel and AMD ROCm GPU. A universal binary.

And even use multiple of these devices at the same time.

hipSYCL reality!

What may sound like a science fiction is now reality in hipSYCL. hipSYCL now has a new compilation flow, that we call generic SSCP compiler. SSCP stands for single-source, single compiler pass. We will discuss what this means later.

To enable the magic, just compile like so:

syclcc --hipsycl-targets=generic -o test test.cpp

In the future, the plan is to make --hipsycl-targets=generic the default, so that this can be omitted as well. But what does it do? Let’s first discuss the state of the art.

Current status quo

Current SYCL implementations, including hipSYCL and DPC++ rely on the single-source, multiple compiler passes (SMCP) model. This means that they invoke a separate SYCL device compiler that parses and compiles the code, and generates a device binary. Afterwards, the usual host compiler is invoked, which again parses and compiles the code for the host, and also ensures that device binaries are embedded in the application. The result is a host binary with embedded device code containing kernels. Compilers for other programming models, such as NVIDIA’s nvcc CUDA compiler or AMD’s HIP compiler, work similarly.

Maybe you have spotted one issue already: The code is parsed multiple times – once for host, and once for device. And with C++ being C++, this can take time.

But it gets worse

But that’s not all there is to it. As it turns out, there is no unified code representation that Intel, NVIDIA and AMD GPU compute drivers can all understand. Intel GPUs want SPIR-V. SPIR-V is supported by neither AMD nor NVIDIA compute drivers. NVIDIA has their own code representation called PTX. AMD GPUs want amdgcn code.

So, if you want to have a binary that runs everywhere, SYCL implementations actually need to invoke the device compiler several times: Once for every code format that is required (PTX, SPIR-V, amdgcn). This means we are already looking at compiling the source code four times: Once for the host, and three times for the GPUs.

But it gets worse (again)

But it’s even worse than that. AMD’s ROCm compute platform does not have a device independent code representation. So, in order to support every AMD GPU, you actually need to compile seperately for each GPU supported by ROCm. My ROCm 5.3 installation can generate code for 38 different AMD GPU architectures (just count the number of ISA bitcode files in the rocm/amdgcn/bitcode directory). This means that in total we are now looking at parsing and compiling code once for the host, once for PTX, once for SPIR-V, and 38 times for AMD. 41 times in total. Clearly this is not practical.

And this approach also does not scale if we think about potentially supporting more backends in the future.

hipSYCL generic SSCP compiler to the rescue!

So, what is this generic SSCP thing? It actually combines two ideas:

- It is a single-pass compiler. This is what SSCP means, and implies that the device code will be extracted during the compilation for host. So, code is only parsed a single time.

- It introduces a generic, backend and device-independent code representation based on LLVM IR. The SSCP compiler stores this code representation in the application. At runtime, hipSYCL will then translate the generic code representation to whatever is needed: PTX, SPIR-V, or amdgcn code for one of the 38 AMD ROCm GPUs. Effectively, this means that we now have a unified code representation across all backends, even if they by themselves do not support one.

The consequence is that we get a binary that can run on all supported devices, while only parsing the code exactly one time – just like a regular C++ compilation.

What are the costs at runtime?

Now you might be asking: Hang on! You are now compiling at runtime, so you have just moved the cost to runtime! But that’s not true: Most likely you don’t have a system that has all of the 41 different GPU architectures installed, such that it wouldn’t have to actually generate code for all these targets. So, the runtime compilation would only compile based on the individual need of the user, but has the capability to run on all 41 GPUs. Additionally, even if you did run on all 41 devices, you’d still have saved parsing the code 41 additional times, because runtime compilation does not involve source code that needs to be parsed.

But there’s another important point: SYCL implementations effectively already do runtime compilation! If a SYCL implementation feeds PTX code to the CUDA driver, the CUDA driver will already compile this PTX code to machine code at runtime. The same is true for SPIR-V code. So, runtime compilation is no new behavior in SYCL, and something that SYCL applications already need to deal with today: It is quite likely that your first kernel launch will take longer due to drivers compiling the kernel on the fly. The additional step that we introduce roughly doubles that existing runtime compilation time. In other words, there’s additional overhead, but it does not change the fundamental order of magnitude of existing runtime compilation costs. If your SYCL application can tolerate current runtime compilation costs, likely it will be able to tolerate the additional step too.

Compile time improvements

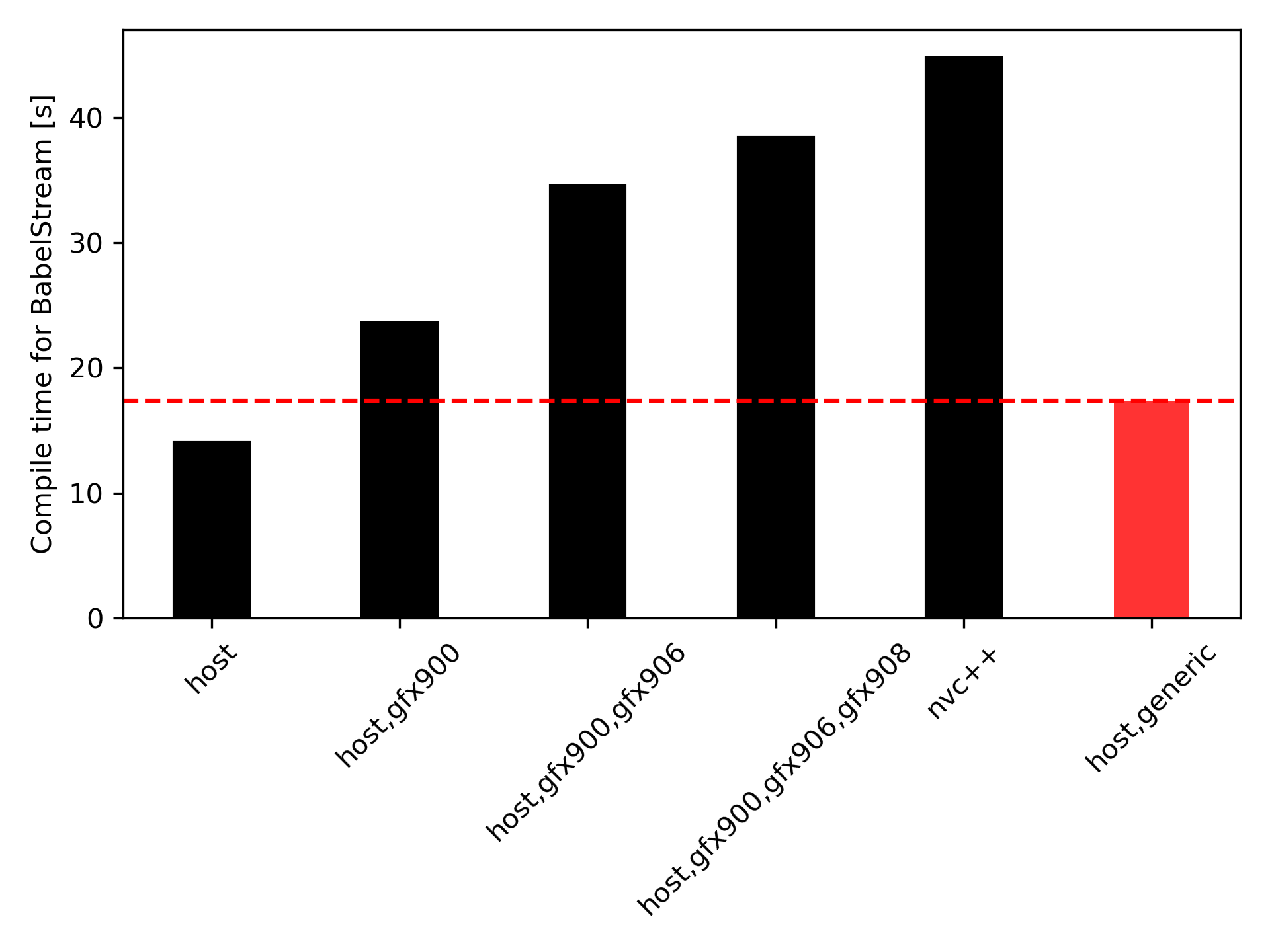

What did it bring? This is shown in this graph, where I’ve measured the time it takes to compile the BabelStream benchmark with various compilation flows in hipSYCL:

The host case describes a regular clang compilation for CPU without specific SYCL compiler logic. This is our baseline. The host,gfx900,… cases correspond to compiling for 1, 2, and 3 AMD GPUs with the old multipass compiler based on the clang HIP toolchain. nvc++ refers to the case where hipSYCL operates as a CUDA library for NVIDIA’s nvc++ compiler.

The host,generic bar shows the time when our new generic SSCP compiler is enabled. As can be seen, the new compiler takes only roughly 15% longer than the host compilation. But it is over twice as fast compared to compiling for the three AMD GPUs with the previous compiler. And remember that the resulting binary supports not only 3 GPUs, but 38 AMD GPUs, plus any NVIDIA GPU, plus any Intel GPU. You can imagine how long it would have taken to build a binary with equal portability with the older hipSYCL compiler, or any other SYCL implementation.

Performance

How does performance look like with the new compiler? The boring answer is: It’s similar to the old one, typically within 10% performance in both directions. So you really get the same kernel performance, but with more portability of the resulting binary, and less compile times. And we have not even started optimizing for performance in particular, as the development focus until now was mainly on functionality.

Conclusion

hipSYCL has a major new feature: A compiler that can generate ultra-portable binaries with less compile time than other approaches and without sacrificing performance. If you want to play with it, it is part of the main hipSYCL repository. It can run some very complex applications, but be aware that a couple SYCL features are not yet implemented because they are still being worked on - in particular atomics, the SYCL 2020 group algorithm library and SYCL 2020 reductions.